GSNadmin

Staff member

Adding a dummy radial engine to your plane is an excellent way to add that scale finishing touch. If you have been a scale modeler for just about any amount of time, you have probably know about Williams Brothers (WB) cylinders and may have even used then from time to time. WB scale accessories are great and to replicate a radial engine of a full scale prototype their products are a great way to accomplish the task. WB also offers more complete kits having a crankcase and a full set of cylinders and related parts and I recently used their 9-cylinder Pratt & Whitney Wasp for my recent 1/6 scale Hall Bulldog racer project.

The molds for the WB engines were designed long before the advent of 3D solid modeling and CAD/CAM machines that are routinely used to produce the molds for today’s plastic models. As such, most of the WB parts come in simple halves made from “old school” molds and therefore don’t have the fit and finish of what we expect today in a modern kit. Nevertheless, these kits are reasonably accurate, have good detail and are readily available. Make no mistake however, if you want a good replica, it’s a lot of work.

Crankcase

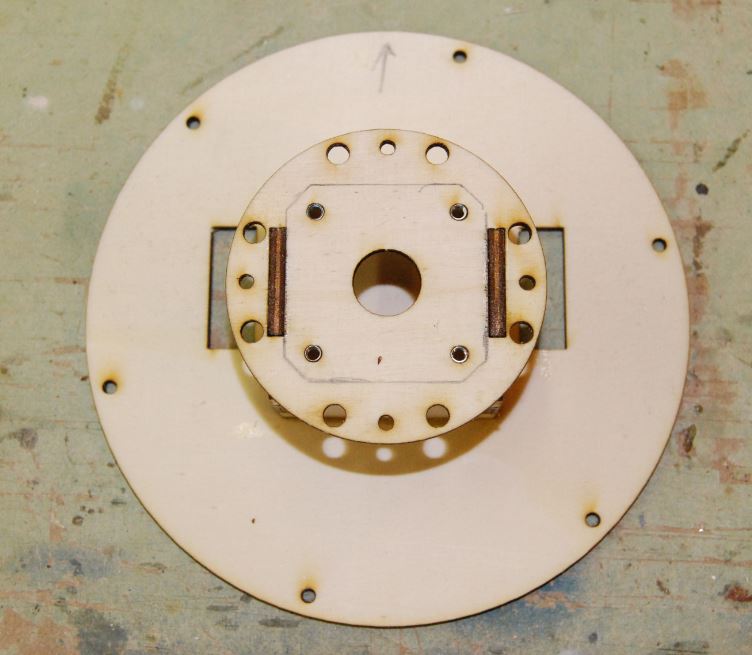

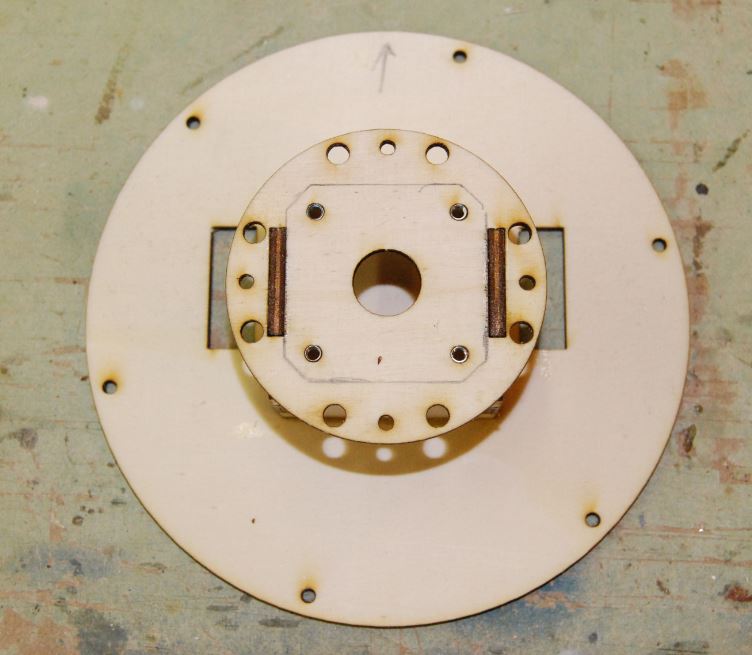

Having already selected the motor for the model, I started by taking some careful measurements and test fitting it against the crankcase to determine if the motor would fit and be fully concealed within. Plus, I had to make provisions to be able to completely remove the dummy engine. While the motor was mounted conventionally to a ply box, I mounted the crankcase to a 1/8” ply plate that, in turn, just slips over the motor’s “X” mount and is bolted to the firewall from behind.

(Above) The dummy engine is bolted in from behind motor mount plate.

This early stage is were all the design thinking had to be done and accessibility was a primary reason that I made the entire power assembly – firewall, cowl, motor and dummy engine – completely removable from the model as a unit. An equally important reason for doing this was to allow access to the internals of the model (servos, battery, pushrods) and to allow the installation of the centrally mounted, sprung landing gear assembly. Looking back, this was an obvious solution but, at the time, it took quite a bit of late night “noodling” to get there!

(Above) A ply plate with blind nuts fits over the motor’s “X” mount.

Once the crankcase was centered, mounted and the prop test fitted, it was all plastic modeling going forward, however a key box to check is whether the fully assembled engine will fit within the cowling. Just like the real Bulldog, the engine was a tight fit in the cowl and this necessitated the removal of the domed-shaped valve covers which were only less than an eighth inch high. Although I covered the resulting holes with sheet plastic, the lack of this detail cannot be seen with the engine installed.

Cylinders

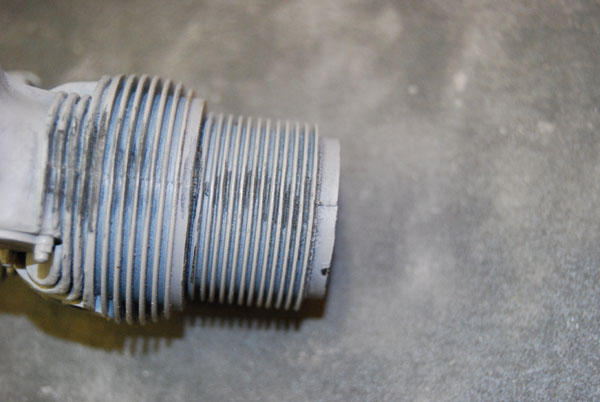

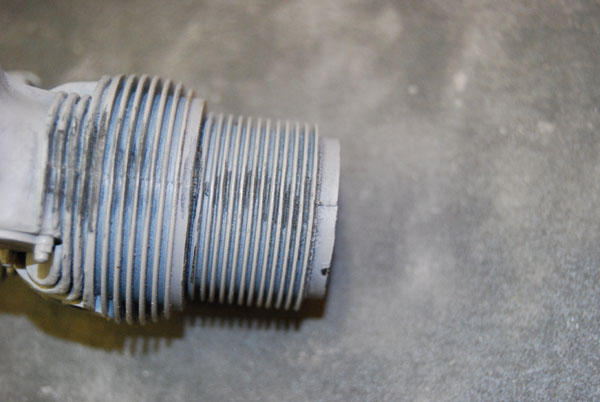

Each of the nine cylinders probably took me about 1-2 hours to properly clean up, assemble and finish. The primary issues are parts fit and seams as the fins, head and valve train have an assembly seam running through them when the two cylinder halves are joined. The fitting issue was dealt with rather easily by first leveling each half of the cylinder using a piece of fine sandpaper temporarily affixed to a sheet of glass with artists adhesive.

(Above) Use plastic nippers to separate the parts from the sprue and sandpaper on a glass plate to true the mating surfaces.

This process will take out the alignment pins, but these don’t really line up anyway. To join the halves, wet the mating surfaces with a heavy dose of liquid plastic cement which works by slightly dissolving the plastic.

(Above) Close-up of the seam running through the assembly.

Wait a few seconds and then press the halves together and, in so doing, forcing out some molten plastic along the seam. I did not use clamps to keep them together, the reason being is that a clamp may cause the assembly to slide out of register.

Let the parts dry overnight, but check them periodically to see that everything is still lined up. This process will create an ugly “outee” seam of plastic around the entire circumference of the assembly, but it is this seam that will help you achieve a proper finish.

(Above) Primer is used to show progress and any remaining seams.

(Above) The top of the head is particularly challenging, however not much of it can be seen once installed on the model.

The time consuming part in all this is cleaning up the cylinder fins. Start by leveling all the fins where they mate by simply sanding them down across the seam. Then use a fine razor saw to clean up and deepen the valleys between each fin. Using a piece of auto-body, self adhesive 220 sandpaper folded with a crisp edge, sand in between all the fins to even them out and to create a contiguous line front to back.

(Above) The cylinder is generally much easier to clean up versus the head.

A spritz of gray primer can be used to check progress although perfectionists may consider silver paint which is terribly unforgiving of surface problems. While tedious, the cylinder area of the assembly is much truer and is therefore easier to clean up than is the head section since it is the latter area where all the fin alignment issues are. Along with the above, I used various shapes of fine jeweler’s files to clean up the head.

(Above) Some of the tools I used to clean up the engine’s fins.

Pushrod tubes

(Above) A good amount of work to install, but the aluminum pushrod tubes are a prominent feature.

Although the kit provides molded pushrod tubes (all 18 of them), each had a seam and a few ejector pin marks in them from the molding process. I therefore elected to make the pushrods out of aluminum, but I felt that the pushrod ends were good enough to use as they were. So, I cut the pushrod tubes in half and spun them on my lathe so that I could drill a hole in each to accept my 1/8” aluminum pushrod tubes. I also cleaned up their seams with a fine file while on the lathe and then carefully cut them free from the shaft.

Now I had 36 parts and I wasn’t done yet. With the cylinders still apart from the crankcase, I drilled out the bosses on the crankcase and on each of the cylinder heads to accept the tubes. Next, I carefully assembled the crankcase and cylinders, making sure that each cylinder was radially oriented on the crankcase. I was careful to watch here for twist and out of true in all three axes.

(Above) The finished nine-cylinder Pratt and Whitney Wasp radial engine.

When dry and after painting and weathering the engine, I then slid the pushrod ends onto my aluminum tube and installed the tube by first sliding it down into the crankcase and then up into the cylinder head. I made sure that none of the tubes fouled the motor hiding within the crankcase. A little CyA at the joint holds it all together.

Other details

I originally had thoughts of being able to display the entire upper half of the engine via removable cowl panels and had therefore planned to install all the intake and exhaust plumbing – which also arrive in halves. Ultimately, I didn’t do this for a couple of reasons. Aside from being a lot more work, I was getting concerned with weight and complexity, I would have had to cut up my carefully finished cowl and make a new mounting system and the parts in question really didn’t fit up that well anyway.

Furthermore, since the cylinders provide a clear path to the innards of the crankcase, I took advantage of this by drilling out all the intake and exhaust ports on the back of the cylinder head to provide an exit for some cooling air. The intake area is comprised of the space around the prop shaft, so the exit area was then much greater and, with the fan on the OS motor, there should be quite a breeze flowing through.

I did do the prominent spark plug caps which are nothing more than sections of telescopic plastic tube. From my photos, it appeared that the Bulldog’s engine was not equipped with high altitude, pressurized, braided cable plug wires for obvious reasons, so I replicated the simpler rubber type with heated and bent sections of plastic rod. Nevertheless, if you’re looking for the braided variety, check into details available for plastic car models.

I mounted the cowling directly to the engine’s cylinders with screws into a ply ring which was in turn screwed into the rear spark plug holes. Not really scale of course, but none of this can be seen. The real airplane had brackets attached to the exhaust manifold for this.

Painting and weathering

I first painted each of the cylinders flat black and then airbrushed on some silver/gray but, for the latter, I held the airbrush at an angle so as not to get much paint in the valleys. I also went a bit heavier on the heads since these are almost always lighter in color than the cylinders themselves. The edges of the fins were then picked out in straight silver to impart some depth. The crankcase was done in straight gray over which I spritzed an extremely light coat of silver.

Only museum pieces show no signs of oil weepage and to show a little on my engine I used various viscosities (and therefore intensities) of burnt umber. I did this everywhere there was a joint – at the base gaskets, the pushrod seals, nuts and bolts – making sure that there was more at the bottom than the top. An airbrush could be used for some of this to show only a breath of oil versus an outright leak, but I mostly used a 000 brush. Make sure the weathering here matches the model – the Bulldog was not flown a lot and was not a warplane so its engine should not have shown a lot of use.

Summary

The Williams Brothers Radial engine in my model wound up being more than just a detail, it became a “model within a model”. Although it was quite a bit of work, assembling and finishing this kit was a lot less work than starting from scratch and, as with any radial-engined aircraft, it’s the focal point of the model.

Materials Used

Tech Tip: A handy tool that I used to clean up the fins and to check progress was a medium firmness brass brush. Use this to clear out sanding debris and to provide some tooth for the paint.

BY ROB CASO

http://www.modelairplanenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/MAN_Button_newsletter_WEB.jpg

http://www.modelairplanenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/MAN_Button_newsletter_WEB.jpg

Model Airplane News - The #1 resource for RC plane and helicopter enthusiasts featuring news, videos, product releases and tech tips.

Continue reading...

The molds for the WB engines were designed long before the advent of 3D solid modeling and CAD/CAM machines that are routinely used to produce the molds for today’s plastic models. As such, most of the WB parts come in simple halves made from “old school” molds and therefore don’t have the fit and finish of what we expect today in a modern kit. Nevertheless, these kits are reasonably accurate, have good detail and are readily available. Make no mistake however, if you want a good replica, it’s a lot of work.

Crankcase

Having already selected the motor for the model, I started by taking some careful measurements and test fitting it against the crankcase to determine if the motor would fit and be fully concealed within. Plus, I had to make provisions to be able to completely remove the dummy engine. While the motor was mounted conventionally to a ply box, I mounted the crankcase to a 1/8” ply plate that, in turn, just slips over the motor’s “X” mount and is bolted to the firewall from behind.

(Above) The dummy engine is bolted in from behind motor mount plate.

This early stage is were all the design thinking had to be done and accessibility was a primary reason that I made the entire power assembly – firewall, cowl, motor and dummy engine – completely removable from the model as a unit. An equally important reason for doing this was to allow access to the internals of the model (servos, battery, pushrods) and to allow the installation of the centrally mounted, sprung landing gear assembly. Looking back, this was an obvious solution but, at the time, it took quite a bit of late night “noodling” to get there!

(Above) A ply plate with blind nuts fits over the motor’s “X” mount.

Once the crankcase was centered, mounted and the prop test fitted, it was all plastic modeling going forward, however a key box to check is whether the fully assembled engine will fit within the cowling. Just like the real Bulldog, the engine was a tight fit in the cowl and this necessitated the removal of the domed-shaped valve covers which were only less than an eighth inch high. Although I covered the resulting holes with sheet plastic, the lack of this detail cannot be seen with the engine installed.

Cylinders

Each of the nine cylinders probably took me about 1-2 hours to properly clean up, assemble and finish. The primary issues are parts fit and seams as the fins, head and valve train have an assembly seam running through them when the two cylinder halves are joined. The fitting issue was dealt with rather easily by first leveling each half of the cylinder using a piece of fine sandpaper temporarily affixed to a sheet of glass with artists adhesive.

(Above) Use plastic nippers to separate the parts from the sprue and sandpaper on a glass plate to true the mating surfaces.

This process will take out the alignment pins, but these don’t really line up anyway. To join the halves, wet the mating surfaces with a heavy dose of liquid plastic cement which works by slightly dissolving the plastic.

(Above) Close-up of the seam running through the assembly.

Wait a few seconds and then press the halves together and, in so doing, forcing out some molten plastic along the seam. I did not use clamps to keep them together, the reason being is that a clamp may cause the assembly to slide out of register.

Let the parts dry overnight, but check them periodically to see that everything is still lined up. This process will create an ugly “outee” seam of plastic around the entire circumference of the assembly, but it is this seam that will help you achieve a proper finish.

(Above) Primer is used to show progress and any remaining seams.

(Above) The top of the head is particularly challenging, however not much of it can be seen once installed on the model.

The time consuming part in all this is cleaning up the cylinder fins. Start by leveling all the fins where they mate by simply sanding them down across the seam. Then use a fine razor saw to clean up and deepen the valleys between each fin. Using a piece of auto-body, self adhesive 220 sandpaper folded with a crisp edge, sand in between all the fins to even them out and to create a contiguous line front to back.

(Above) The cylinder is generally much easier to clean up versus the head.

A spritz of gray primer can be used to check progress although perfectionists may consider silver paint which is terribly unforgiving of surface problems. While tedious, the cylinder area of the assembly is much truer and is therefore easier to clean up than is the head section since it is the latter area where all the fin alignment issues are. Along with the above, I used various shapes of fine jeweler’s files to clean up the head.

(Above) Some of the tools I used to clean up the engine’s fins.

Pushrod tubes

(Above) A good amount of work to install, but the aluminum pushrod tubes are a prominent feature.

Although the kit provides molded pushrod tubes (all 18 of them), each had a seam and a few ejector pin marks in them from the molding process. I therefore elected to make the pushrods out of aluminum, but I felt that the pushrod ends were good enough to use as they were. So, I cut the pushrod tubes in half and spun them on my lathe so that I could drill a hole in each to accept my 1/8” aluminum pushrod tubes. I also cleaned up their seams with a fine file while on the lathe and then carefully cut them free from the shaft.

Now I had 36 parts and I wasn’t done yet. With the cylinders still apart from the crankcase, I drilled out the bosses on the crankcase and on each of the cylinder heads to accept the tubes. Next, I carefully assembled the crankcase and cylinders, making sure that each cylinder was radially oriented on the crankcase. I was careful to watch here for twist and out of true in all three axes.

(Above) The finished nine-cylinder Pratt and Whitney Wasp radial engine.

When dry and after painting and weathering the engine, I then slid the pushrod ends onto my aluminum tube and installed the tube by first sliding it down into the crankcase and then up into the cylinder head. I made sure that none of the tubes fouled the motor hiding within the crankcase. A little CyA at the joint holds it all together.

Other details

I originally had thoughts of being able to display the entire upper half of the engine via removable cowl panels and had therefore planned to install all the intake and exhaust plumbing – which also arrive in halves. Ultimately, I didn’t do this for a couple of reasons. Aside from being a lot more work, I was getting concerned with weight and complexity, I would have had to cut up my carefully finished cowl and make a new mounting system and the parts in question really didn’t fit up that well anyway.

Furthermore, since the cylinders provide a clear path to the innards of the crankcase, I took advantage of this by drilling out all the intake and exhaust ports on the back of the cylinder head to provide an exit for some cooling air. The intake area is comprised of the space around the prop shaft, so the exit area was then much greater and, with the fan on the OS motor, there should be quite a breeze flowing through.

I did do the prominent spark plug caps which are nothing more than sections of telescopic plastic tube. From my photos, it appeared that the Bulldog’s engine was not equipped with high altitude, pressurized, braided cable plug wires for obvious reasons, so I replicated the simpler rubber type with heated and bent sections of plastic rod. Nevertheless, if you’re looking for the braided variety, check into details available for plastic car models.

I mounted the cowling directly to the engine’s cylinders with screws into a ply ring which was in turn screwed into the rear spark plug holes. Not really scale of course, but none of this can be seen. The real airplane had brackets attached to the exhaust manifold for this.

Painting and weathering

I first painted each of the cylinders flat black and then airbrushed on some silver/gray but, for the latter, I held the airbrush at an angle so as not to get much paint in the valleys. I also went a bit heavier on the heads since these are almost always lighter in color than the cylinders themselves. The edges of the fins were then picked out in straight silver to impart some depth. The crankcase was done in straight gray over which I spritzed an extremely light coat of silver.

Only museum pieces show no signs of oil weepage and to show a little on my engine I used various viscosities (and therefore intensities) of burnt umber. I did this everywhere there was a joint – at the base gaskets, the pushrod seals, nuts and bolts – making sure that there was more at the bottom than the top. An airbrush could be used for some of this to show only a breath of oil versus an outright leak, but I mostly used a 000 brush. Make sure the weathering here matches the model – the Bulldog was not flown a lot and was not a warplane so its engine should not have shown a lot of use.

Summary

The Williams Brothers Radial engine in my model wound up being more than just a detail, it became a “model within a model”. Although it was quite a bit of work, assembling and finishing this kit was a lot less work than starting from scratch and, as with any radial-engined aircraft, it’s the focal point of the model.

Materials Used

- Testors plastic cement,

- ZAP CyA

- Tamiya primer, Testor’s Model Master enamel

- Evergreen tube and sheet

- K&S Engineering Aluminum tube

- 3M Acryl Blue Filler

- Sandpaper

- 3M self adhesive

Tech Tip: A handy tool that I used to clean up the fins and to check progress was a medium firmness brass brush. Use this to clear out sanding debris and to provide some tooth for the paint.

BY ROB CASO

http://www.modelairplanenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/MAN_Button_newsletter_WEB.jpg

http://www.modelairplanenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/MAN_Button_newsletter_WEB.jpgModel Airplane News - The #1 resource for RC plane and helicopter enthusiasts featuring news, videos, product releases and tech tips.

Continue reading...